What are Codecs and Containers? What’s the difference and how do they work?

In the multimedia world, a codec performs encoding and decoding of video or audio signals. A container wraps that encoded video and audio together with additional information used to identify, interleave, and synchronize them.

There is quite a lot of complexity in multimedia. Sometimes the same term is used to mean different things, which makes it very easy to mix up concepts and get lost. On top of that, there are many different codecs, containers, and file formats. Part of this ambiguity comes from a lack of strict standardization, but also from the fact that multimedia itself is far from trivial.

What is a Codec?

Generally speaking, a codec is hardware, software, or a combination of both that transforms a signal or data stream from its original form into a format suitable for transmission or storage (encoding), and back again (decoding).

There is no single strict definition of a codec. The term can be applied to both analog and digital signals.

Let’s look at both cases and see how they differ.

Analog Signal Coding

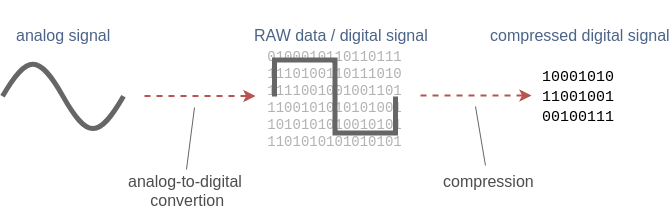

When we talk about analog signals, such as human voice, we can (though it’s not very common) refer to the hardware circuitry that performs analog-to-digital (ADC) and digital-to-analog (DAC) conversion as a codec.

For example, such a device may implement the PCM (Pulse-Code Modulation) method to encode an analog signal into a RAW digital data stream so it can be digitally recorded. During playback, the digital data is decoded back into an analog signal so we can hear it.

For video, after analog-to-digital conversion we obtain a sequence of RAW images, for example in RGB 4:4:4 or YUV 4:2:2 formats.

This may sound counterintuitive, but although RAW digital data is usually considered uncompressed, in practice it can already involve some form of compression. This happens because information may be lost during the analog-to-digital conversion. In many cases, conversion parameters can be chosen so that the data loss is negligible and can safely be ignored.

For audio, two key parameters are:

- Sample size, which determines how many bits are used to represent each audio sample.

- Sample rate, which defines how many times per second the audio signal is measured.

Lower values generally result in lower quality and smaller data size.

For video, we have similar characteristics to still images:

- Resolution (width × height in pixels)

- Bit depth (amount of color information per pixel)

- Color space (for example, RGB or YUV)

In addition, video has a frame rate, which defines how many images are captured per second.

In summary, after analog-to-digital conversion we obtain so-called RAW digital data. We typically treat it as uncompressed. While some information loss may already occur at this stage, we usually don’t refer to this as compression. Further encoding with more advanced algorithms is then used to achieve much higher compression ratios.

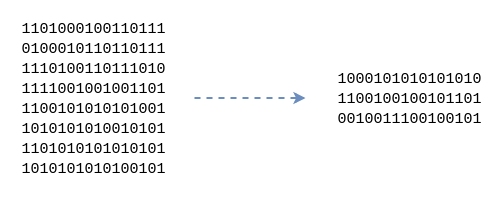

Digital Signal Coding

When we talk about an already digital signal, audio or video, a codec is a hardware component or software program that performs compression and decompression (and sometimes encryption and decryption) of a digital data stream. There is a wide variety of coding algorithms, each differing in complexity, efficiency, and compression ratio.

Taking the digitally sampled voice from the previous section as an example, we may want to compress it to reduce bandwidth usage or storage requirements. We could encode it using formats such as MP3 or AAC and store it in a file. Similarly, video data could be encoded using a format like VP9.

A codec combines both an encoder and a decoder. When only one of these functions is present, we usually refer to it explicitly as an encoder or a decoder. For example, a digital camera may contain an H.265 encoder, while a smartphone typically contains both an H.265 encoder and decoder.

Lossless and Lossy Compression

Digital compression can be lossless or lossy.

Lossless compression reduces data size in a way that allows the original signal to be perfectly reconstructed, with no loss of quality.

Lossless compression reduces data size in a way that allows the original signal to be perfectly reconstructed, with no loss of quality.

There are very few truly lossless video codecs in common use, but lossless audio codecs are relatively popular.

Lossy compression sacrifices some quality to achieve much higher compression ratios and smaller data sizes.

Lossy compression sacrifices some quality to achieve much higher compression ratios and smaller data sizes.

Almost all video codecs are lossy. For audio, both lossy and lossless formats are widely used.

Since the same digital signal can be encoded in many different ways, a formal description of how encoding and decoding work is required. This description is provided by a coding format specification.

What is a Coding Format?

A coding format (sometimes called a compression format) is a specification that defines how encoding and decoding should be performed. There are many different approaches to compressing audio and video, and many of them have been standardized.

For example, H.264 is a video coding standard, while AAC is an audio coding standard. Below are some of the most widely used coding formats today.

Video Coding Formats

- H.264 – AVC (Advanced Video Coding), also known as MPEG-4 Part 10. As of 2019, it is the most widely used and broadly supported video coding standard. First published in 2003 and still a core technology. Supported by all major browsers.

- H.265 – HEVC (High-Efficiency Video Coding), also known as MPEG-H Part 2. The successor to H.264, offering roughly 25–50% better compression. First published in 2013. Supported in Safari, but not in Chrome.

- VP9 – An open, royalty-free format developed by Google. It competes mainly with H.265 and has broader browser support on the Web. Supported in Chrome, but not in Safari.

- AV1 – An open, royalty-free format designed as a next-generation Internet video standard. It offers over 20% better compression than VP9 and H.265, and more than 50% better than H.264. AV1 adoption is still in its early stages.

- H.266 – VVC (Versatile Video Coding), also known as MPEG-I Part 3. A future standard intended as the successor to H.265.

Audio Coding Formats

- MP3 – MPEG-2 Audio Layer III. A very popular but relatively old audio format, first released in 1993. Supported by all major browsers.

- AAC – Advanced Audio Coding. The successor to MP3, introduced in 1997. It generally provides better quality than MP3 at the same bit rate. Supported by all major browsers.

- FLAC – Free Lossless Audio Codec, providing lossless audio compression.

- Vorbis – A free and open-source audio format created by the Xiph.Org Foundation.

- Opus – A free audio codec designed for low-latency, real-time interactive communication. Widely supported by modern browsers.

- G.722 – An ITU-T audio coding standard approved in 1988. Its patents have expired, making it freely available. Some real-time conferencing systems, including WebRTC implementations, still support it.

Codec vs. Coding Format

There is often confusion between the terms codec and coding format. A coding format is a specification, while a codec is an implementation of that specification. For example, H.264 is a coding format, whereas x264 and OpenH264 are software codecs that implement it. Implementations can be hardware-based, software-based, or both.

Keeping this distinction in mind helps, although in everyday usage the terms are often used interchangeably.

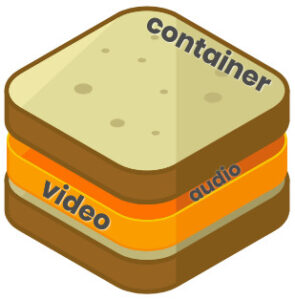

What is a Container?

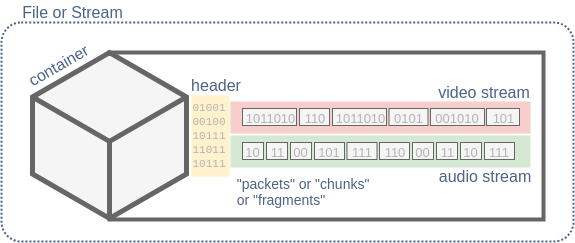

A container (also called a media container or digital container format) is a wrapper that holds one or more encoded data streams together with metadata describing how those streams should be interpreted and synchronized.

If you take the raw bitstream output of an H.264 encoder and simply save it to a file, another user may not know what it contains or how to play it. A container solves this by wrapping the bitstream and adding the necessary metadata.

Another key role of a container is to store multiple encoded streams, or tracks. A typical video includes both video and audio streams, along with timing information to keep them synchronized. Containers usually split streams into packets (also called chunks, atoms, or segments) and assign timestamps to them so a player knows exactly when each piece of audio or video should be decoded and played.

Most containers support at least one video stream and one audio stream, and many can also carry additional streams such as subtitles or closed captions. Some containers allow multiple audio tracks, for example to support different languages.

Media container formats vary widely. Some support only a limited set of codecs, while others are designed to handle almost any type of media data. Some are optimized for Internet use, while others are more common in broadcasting or local playback.

Well-known Media Containers

- MP4 – MPEG-4 Part 14, usually with the

.mp4extension. Very popular on the Web and widely used with HTML5 video. Commonly contains H.264 or H.265 video and AAC audio, though it is not limited to these codecs. - Matroska – A free and open container format, typically using the

.mkvextension. Designed to support virtually any audio or video codec. - WebM – A royalty-free container format based on Matroska, using the

.webmextension. Sponsored by Google and intended for HTML5 video. Typically contains VP8/VP9 or AV1 video and Vorbis or Opus audio. - MPEG-TS – MPEG Transport Stream, usually with the

.tsextension. Widely used in DVB and IPTV systems. Commonly carries H.264/H.265 video and AAC audio. - FLV – Adobe’s Flash Video container. With Flash now deprecated, FLV is largely obsolete, though it may still be used with the RTMP streaming protocol.

- AVI – Audio Video Interleave, introduced by Microsoft in 1992. An older container format with many limitations addressed by more modern containers.

Streaming Media

Most coding formats can be used for streaming. While containers are often defined as file formats, many of them also support streaming media, meaning the same container structure can be used to deliver data continuously over a network.

Examples include:

- MPEG-TS, which can be saved as a

.tsfile or streamed live over TCP, UDP, or SRT. - MP4 or MPEG-TS segments delivered over HTTP using MPEG-DASH or HLS.

- FLV, which can be streamed using the RTMP protocol.

While any file can technically be sent over a network, this is often inefficient for low-latency live streaming or conferencing. In such cases, specialized streaming protocols like RTMP, SRT, or RTP are typically used.

In some scenarios, media can even be transmitted without a traditional container. A notable example is WebRTC, which uses the RTP protocol to transport audio and video in separate streams. Instead of a container, RTP relies on payload format specifications that describe how specific codecs are carried. For example, RFC 6184 defines H.264 over RTP, and RFC 7587 defines Opus.

Codecs, Containers, and Licensing

Although codecs and containers are closely related, they are fundamentally different concepts. Despite the large number of available formats, two major ecosystems can be identified:

- MPEG patented standards such as H.264, H.265, and AAC, typically used with the MP4 container. Using these formats in commercial products often requires paying licensing fees to MPEG LA.

- Royalty-free open standards such as VP8/VP9/AV1 and Opus/Vorbis, commonly used with Matroska or WebM containers.

Licensing details can be complex and are an important consideration when choosing formats for a product.

The Future of Codecs and Containers on the Web

Browser and device support for codecs is still fragmented. For example, Chrome supports H.264 and VP8/VP9 but not HEVC, while Safari supports H.264 and HEVC but not VP8/VP9. Similar differences exist for audio codecs such as AAC, Vorbis, and Opus.

As a result, content providers often need to supply the same media in multiple formats to ensure compatibility across devices, which increases complexity and operational cost. One goal of the Alliance for Open Media is to address this problem.

The Alliance is developing the royalty-free AV1 codec, designed to be supported across Web technologies such as HTML5 video and WebRTC. Its members include Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Cisco, Facebook, and others.

In the long term, traditional broadcasting may continue to rely on MPEG standards, while Internet delivery increasingly moves toward open, royalty-free formats.

Summary

We’ve seen how audio and video are encoded and then packaged into containers for storage or transmission. We discussed the difference between codecs and coding formats, as well as the role of containers. Finally, we reviewed some of the most popular codecs and container formats in use today.

With this understanding, navigating multimedia formats and technologies should feel more approachable and predictable.